Introduction

Typically, applying a detour to a method on any typical processor is a trivial task with many possible options. However, when working with the Java Virtual Machine, a bit more work is required in both the research and implementation stages.

I originally wrote this post a few years ago, when I finalized my very first iteration of a Java method hooking library. At the time I thought the method I came up with was great and effective, but looking back at it now, I realize that it was a bit over-engineered and could have been done in a much simpler way while also maintaining the performance of the method.

If you don’t care much about the explanation, you can skip right ahead to the code and tests on my Github here: https://github.com/SystematicSkid/java-jit-hooks

You can find a demo here.

Key Terms

Before I dive into the technical details of this post, I’d like to define a few key terms that will be used throughout the post. If you’re already familiar with the JVM and its internals, feel free to skip this section.

- JVM – Java Virtual Machine

- JNI – Java Native Interface

- JIT – Just-In-Time Compiler

- Hot Method – A method that is invoked frequently

- Stale Method – A method that is invoked infrequently

- C1 – Basic compiler

- C2 – Optimizing compiler

- Tiered Compilation – The process of compiling a method from the interpreter state to C1, then to C2

- CompileBroker – The JVM’s internal compiler process manager

Compiler Process

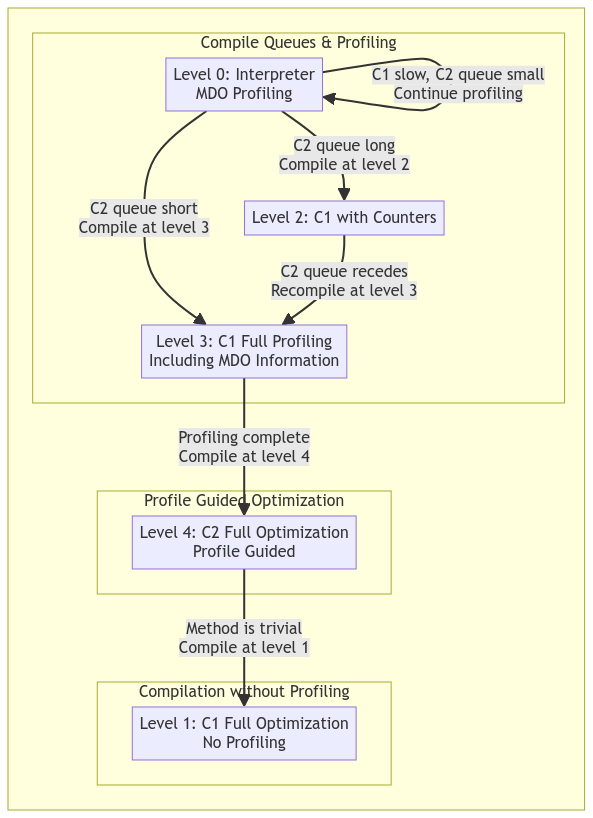

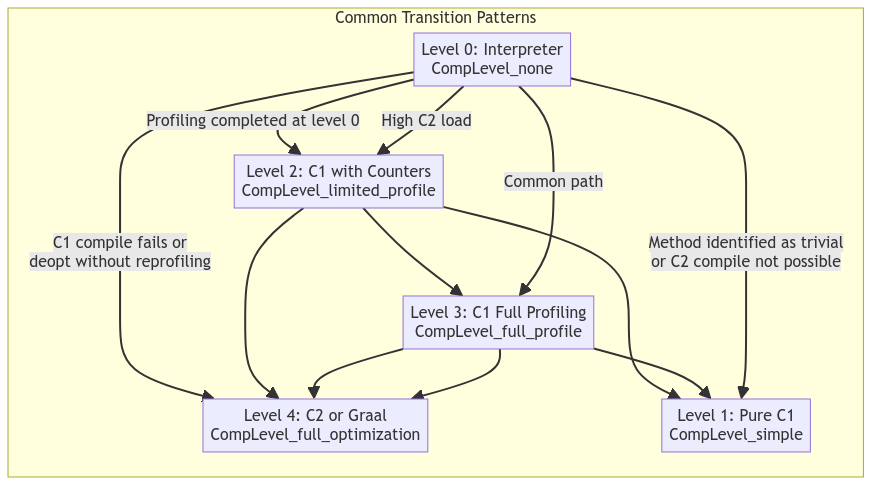

When the Java Virtual Machine is running, all methods are compiled in a tiered and need-based fashion. All methods begin in an interpreter state, where the JVM will directly read the bytecode of the method and execute it. If, however, the CompileBroker decides that the method is being invoked frequently enough, based on the current compilation policy, it will put the method in the queue to be compiled into the next tier, which will usually be the C1 compiler. Feel free to refer to the graph below for a basic explanation of how the compilation process works; keep in mind that the JVM can skip stages and even jump straight from interpreted to C2 if it deems the method to be hot enough.

In a typical Java application, user code will likely never be compiled from the interpreter state into JIT code unless it is either very loop-heavy or is being invoked very frequently. There are a handful of Java methods that will always be compiled upon startup due to their frequent and immediate use behind the scenes.

There are five tiers of execution in the JVM, which are as follows:

- Interpreter

- C1 ( Simple JIT )

- C1 with invocation profiling

- C1 with full profiling

- C2 ( Full optimization )

As mentioned previously, the interpreter is the default execution tier for nearly all methods, and any method can be deoptimized at any time back into the interpreted state. I’ll mention more about the deoptimization process later and how it may affect any hooks placed on these methods.

For the compiler to determine the level of optimization to apply to a method, it will first need to profile the method. This is done via the MethodCounters class, which is a part of the internal Method class in the JVM. The MethodCounters class is a simple class that holds a small integer to count how many times the method has been invoked. Depending on the current tier of execution, the counter may increment instantaneously or periodically. In some tiers of execution, the compiler broker has determined that the method is already in the best state of execution and will disable profiling, removing some overhead.

If a method is both JIT compiled and has profiling enabled, you can peek into the JITd code and see a small snippet of code which will increment the counter.

Accessing JIT Code

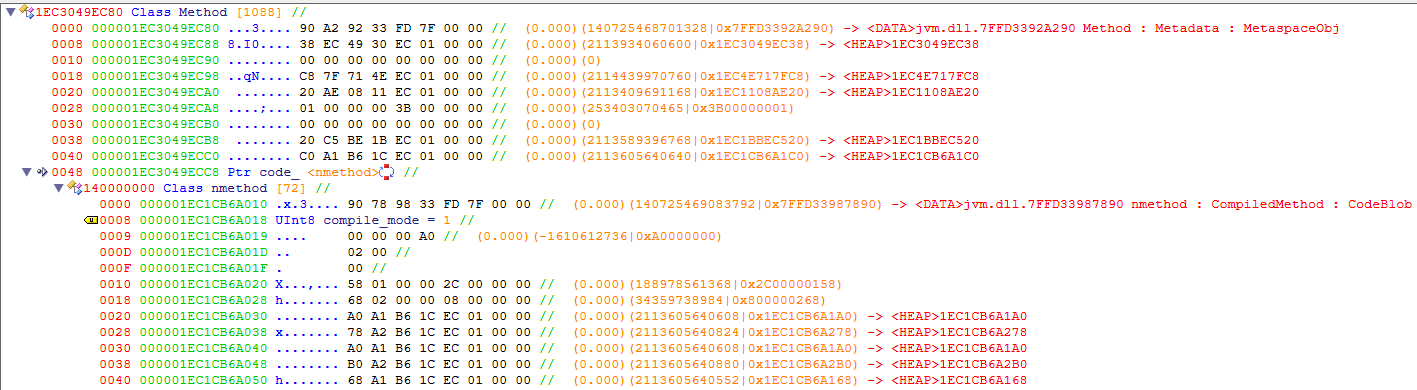

To hook a method’s JIT-compiled code, we first need to find it. There are many ways to access a method within the JVM, but the most documented and reliable method would be to simply use the built-in Java Native Interface (JNI). Using JNI returns a jmethodID, which is just a handle pointing to the compiled method pointer. Most distributions of the JVM come with RTTI enabled, which means that the Method class and subsequent pointers will be easy to identify using a tool like ReClass.

It should be noted that the pointer to the currently installed code block will only exist if the method is not in the interpreter state. Once the code is installed, the Method class will point to a code blob which contains the JIT compiled code as well as some information about the method. As shown in the screenshot, the method I am looking at has been compiled by the C1 compiler in a non-profiled state.

The code blob containers pointers to the start and end of the code as well as any related data. It’s important to note that the executed code is located directly within the CodeBlob class, and not in a new or separate memory region, which means all the code in the blob is self-contained and executable.

Analyzing JITd Code

For the following examples I will be showing the disassembly of the following Java Method, where fps is an integer field in the class:

public int getFps() {

return fps;

}

C1 Compiler

00000297DC2674A0 | mov r10d,dword ptr ds:[rdx+8] | Access compressed class pointer

00000297DC2674A4 | shl r10,3 |

00000297DC2674A8 | cmp r10,rax | Inline cache check

00000297DC2674AB | jne 297DB301080 | _ic_miss_stub

00000297DC2674B1 | nop word ptr ds:[rax+rax],ax |

00000297DC2674BC | nop | Align entrypoint

00000297DC2674C0 | mov dword ptr ss:[rsp-7000],eax | Create stack bang

00000297DC2674C7 | push rbp | Save rbp

00000297DC2674C8 | sub rsp,30 | Create frame

00000297DC2674CC | mov rax,88C90830 | Main ! Static Field: Main.main

00000297DC2674D6 | mov eax,dword ptr ds:[rax+98] | int ! Field: Main.fps

00000297DC2674DC | add rsp,30 | Destroy frame

00000297DC2674E0 | pop rbp | Restore frame

00000297DC2674E1 | cmp rsp,qword ptr ds:[r15+348] | Ensure stack integrity

00000297DC2674E8 | ja 297DC2674EF | Jump to safepoint if smashed

00000297DC2674EE | ret | Return

00000297DC2674EF | mov r10,297DC2674E1 | Safepoint

00000297DC2674F9 | mov qword ptr ds:[r15+360],r10 |

00000297DC267500 | jmp 297DB307A00 |

C2 Compiler

000002EE0835C900 | mov r10d,dword ptr ds:[rdx+8] | Access compressed class pointer

000002EE0835C904 | shl r10,3 |

000002EE0835C908 | cmp rax,r10 | Inline cache check

000002EE0835C90B | jne 2EE074A1080 | _ic_miss_stub

000002EE0835C911 | nop |

000002EE0835C914 | nop dword ptr ds:[rax+rax],eax | Align entrypoint

000002EE0835C91C | nop |

000002EE0835C920 | sub rsp,18 | Create frame

000002EE0835C927 | mov qword ptr ss:[rsp+10],rbp | Preserve frame

000002EE0835C92C | mov r10,88C85F98 | Main ! Static Field: Main.main

000002EE0835C936 | mov eax,dword ptr ds:[r10+98] | int ! Field: Main.fps

000002EE0835C93D | add rsp,10 | Destroy frame

000002EE0835C941 | pop rbp | Restore frame

000002EE0835C942 | cmp rsp,qword ptr ds:[r15+348] | Ensure stack integrity

000002EE0835C949 | ja 2EE0835C950 | Jump to safepoint if smashed

000002EE0835C94F | ret | Return

000002EE0835C950 | mov r10,2EE0835C942 | Safepoint

000002EE0835C95A | mov qword ptr ds:[r15+360],r10 |

000002EE0835C961 | jmp 2EE074A7A00 |

Analysis

Both methods are nearly identical, which makes sense since the original code is so simple. The main differences between the C1 and C2 compilers in this case, and the reason I am showing them, are the frame creation and stack bang applied. The stack bang is an easily identifiable instruction that is used to ensure that the stack is in a valid state and will be later used to determine if the stack has been smashed.

There are a few important things here to note: The first few instructions which check and ensure that the instance class passed to the function matches the expected class is only called when executing this method from native code. This means that placing a breakpoint there will result in the breakpoint likely never being called.

Another interesting thing to note is that the static instance of the class is inlined into the method itself. This was a decision by the compiler, which is odd since the rdx register already holds the instance pointer. I am aware that the instance pointer will never change, but it’s still odd that the compiler would choose to do this.

The stack bang, or the frame creation in the context of a C2 compiled method, is the real entrypoint for invocation from Java code, whether that be from an interpreted method being handled via the template table or from another JIT-compiled method. Placing a breakpoint here will result in the breakpoint being hit every time the method is invoked, regardless of the callee’s state.

Hooking

At this point, we should have a good understanding of how to detour the execution of this method, but there are still some issues. I opted to do a simple 12-byte detour which looks like this:

mov reg, address_of_detour

jmp reg

From what I have seen it seems like there will always be at least 12 bytes of free space.

If we leave the code as is, however, there will be the remaining issue of the custom Java calling convention still being in use. The calling convention is described below:

|-------------------------------------------------------|

| c_rarg0 c_rarg1 c_rarg2 c_rarg3 c_rarg4 c_rarg5 |

|-------------------------------------------------------|

| rcx rdx r8 r9 rdi rsi | windows

| rdi rsi rdx rcx r8 r9 | solaris/linux

|-------------------------------------------------------|

| j_rarg5 j_rarg0 j_rarg1 j_rarg2 j_rarg3 j_rarg4 |

|-------------------------------------------------------|

If you simply detour to your callback then you have a chance of corrupting non-scratch registers and causing a crash. To avoid this, we need to create a custom wrapper for our callback which will handle the custom calling convention and provide an easy way for us to access arguments and return values.

In my tests, I opted to create a very basic naked shell that simply pushed all the args onto the stack and passes the stack pointer to the callback which gives free access to all registers. There are likely much more elegant ways to handle this, and I implore you to find a better way if you can.

You can see the shell I used for testing below:

; Naked function, so no prologue or epilogue generated by the compiler

; Note: Does not preserve XMM registers

naked_shell PROC

; Push all registers

push rax

push rbx

push rcx

push rdx

push rsi

push rdi

push r8

push r9

push r10

push r11

push r12

push r13

push r14

push r15

pushfq ; Push the flags register

; Prepare for the subroutine call

mov rcx, rsp

; Allocate space on stack for all registers and flags

sub rsp, 28h

; Call subroutine at callAddress

mov r10, 100000000h ; Replaced with the address of the callback

call r10

; Deallocate the space on the stack

add rsp, 28h

; Restore the registers and flags

popfq

pop r15

pop r14

pop r13

pop r12

pop r11

pop r10

pop r9

pop r8

pop rdi

pop rsi

pop rdx

pop rcx

pop rbx

; Check if r10 = 1

cmp r10, 1

; Branch to next_hook if r10 = 1

je next_hook

; Restore rax if we are not branching

pop rax

; Jump to the original function (or the next hook)

mov r10, 100000000h ; Replaced with the address of the next hook

jmp r10

; Label to ret instead of jmp

next_hook:

; Simulate pop

add rsp, 8

ret

naked_shell ENDP

This hook allows for fairly simple access to the arguments as well as modification of the return value. The only issue with this shell is that it does not preserve the XMM registers, which means that if the method you are hooking uses them, you will need to preserve them yourself.

Within the JVM assembler, the registers r10 and r11 are considered scratch registers. This means you are free to, and should, leverage these registers for your use. In my case, I used r10 to store the address of the callback and r11 to store the address of the original method/trampoline which is used to restore the original code.

Considerations

At this point, you’re good to hook most methods with ease and modify parameters as you wish. However, there are a few things to keep in mind when hooking methods in the JVM.

Deoptimization

If a method becomes stale, the JVM may deoptimize it, and if this is the case, then your hook will be removed and the compiler will resort to using the interpreter state. This is not a huge issue, but it’s something to keep in mind. This can be prevented using some internal hooks to the JVM state, or you can likely set specific access flags on the method to prevent it from being deoptimized.

I have only run into this issue when forcing a stale method to be compiled into the C2 state, which is not a common occurrence. The JVM will decide to unlink the method and deoptimize it. When compiling the same method into a simple C1 state, I did not re-encounter this issue.

Inlining

Depending on a multitude of factors and the current compilation policy, the JVM can decide to inline any method into another to prevent the overhead of a function call. This is likely one of the most common issues you may encounter if you are calling a small method. To prevent this, you can set the CompileCommand::DontInline flag on the method, which will prevent the JVM from inlining it. This is not a foolproof method, however, and the JVM can still decide to inline the method if it deems it necessary.

To fully prevent this, it may be necessary to research more into the CompilationPolicy event system.

Compiling

There is a high chance that a method you want to hook will not be compiled. There are dozens of ways to force the compilation of a method. If there is not a critical need to receive the invocation of a method, you can access the MethodCounters object and set both the invocation counter and backedge counter to 255, which will force the JVM to throw an invocation_overflow event the next time the method is called, forcing compilation.

If you need to force the compilation of a method immediately, you can hook the CompileBroker and insert your method into the compile queue manually. This is a bit more complicated and requires you to find the CompileBroker in your target JVM, but it is a viable option.

State Changing

As described above, the execution state of a method can change at any time. If a method you have hooked is either optimized or has profiling disabled on it, then the code blob that was previously hooked will be destroyed and a new one will be created. This means that you will need to re-hook the method every time the state changes.

Keep in mind there are likely dozens of ways to achieve all of this within the JVM, and I have only covered a few of them.

Conclusion

I did a lot of work on Java Hooks in the past, but I consider my old methods of hooking the interpreter very cool, but also very over-engineered and detrimental to the performance of the JVM. I may still write a post about it in the future, but I think that this method is just better overall if your only goal is to intercept events or spoof return results. If you want to achieve more with this method, I highly suggest you use a debugger to poke around and see what you can achieve. I have only scratched the surface of what is possible with this method.

I had time this last weekend to revisit the topic of Java Hooks and decided to look more into the JIT system and how it works, which is why you can read this post right now.

P.S.

This was published on Christmas day, so Merry Christmas to anyone who reads this. I hope you have a great holiday season and a happy new year.